Exploring the Northeast’s Growing Local Grain Economy

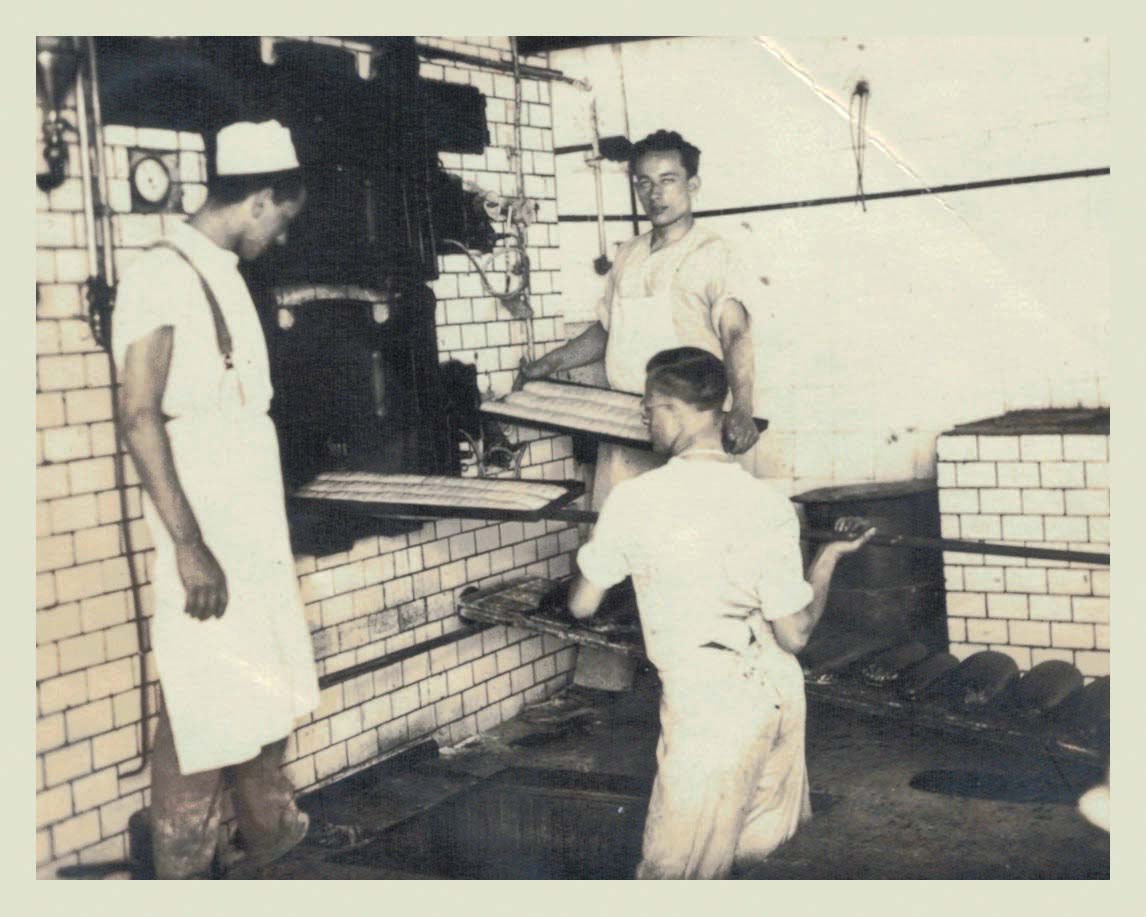

A young Karl at the bakery

In 1929, Karl Oechsner immigrated from Zeil am Main, Germany to the United States. He had served as a baker’s apprentice in Wurzburg and his master baker status enabled his uncle to sponsor his visa. Karl worked for his uncle’s bakery on Myrtle Avenue in Brooklyn for two years to pay o the costs of immigrating and then worked as the head baker at Sing-Sing Prison in Ossining, New York. He later served as the head baker at Ossining’s Ascherman’s Bakery where he worked for the rest of his life.

Karl’s grandson, or Oechsner, has fond memories of the bakery and his grandfather’s famous Christmas Stollen. or is the founder and owner of Oechsner Farms, a USDA Certified Organic Farm located in the Finger Lakes Region of New York, southwest of Ithaca in the small town of Newfield. He currently farms 1,200 acres of organic field crops, focusing on food-grade grain fit for baking, malting, and distilling.

Thor got a taste of what life could be like as a farmer through his uncle who was a dairy farmer in Pennsylvania. Thor majored in agriculture at Cornell University and worked at a different dairy farm immediately after college. It was at the dairy farm where Thor realized how important it is to grow organically. He had an a-ha moment one day while he was spraying corn and was traveling along on a tractor in a Tyvek suit and mask. He was spraying the edge of the field when he looked over to see his well-head five feet from the edge. “I thought, I’m probably drinking this toxic stuff,” and wondered how he did not see or think of that earlier. He had just been accepting the status quo.

He went home and thought that there had to be a better way to farm that was not toxic. He went to the library and read an article in The Atlantic by Wes Jackson, co-founder of The Land Institute, about growing wheat sustainably. Thor wrote to Wes, and after exchanging letters and ideas about sustainable growing practices, Thor vowed that if he ever got into farming again, he would not use synthetic chemicals.

Thor spent a handful of years owning a Volkswagen Audi Repair Business in Ithaca before returning to the fields. He started his farm in 1991, growing vegetables on just ¼ acre. He slowly began farming more land – one acre, then three, then five before renting fifteen acres that became available right up the road. He bought a bigger tractor, a pull-behind combine harvester, a seed cleaner, and then realized there was no going back. His goal was to farm full-time, and he was able to achieve that goal around 2004. Self-described as “totally hell-bent,” Thor slowly picked up land until he got to the farm’s present size. Thor grows a variety of crops including Warthog hard red winter wheat, Danko rye, soft white winter wheat, corn, hard red spring wheat, and buckwheat along with cover crops of clover and a rotation of soybeans. In addition to farming, Thor is co-owner of Farmer Ground Flour and Wide Awake Bakery. He co-created these ventures to minimize risk – he has stakes in each part of the supply chain from farm to end-product. He loves the community which has grown from these efforts.

“It has much more flavor, much more nutritional density, and those are probably the two biggest reasons that I do it. You taste the difference.” —Nicolas Imbriglio

(top left)Beautiful pasta from Passionately Pasta; (top right)at work on Oechsner Farm; (bottom left)close up of grain at Oechsner Farm; (bottom right)more pasta courtesy of Passionately Pasta

Thor also supplies grain to Ground Up Grain, a mill based in Hadley, Massachusetts which specializes in stone milled flours. Coowner and co-founder Andrea Stanley started Ground Up Grain with her husband Christian in 2019 and is passionate about working with small-scale farms in the Northeast. She primarily works with farmers that are within a 250-mile radius of the mill. Ground Up Grain is in the process of pursuing USDA Organic Certification, but Andrea shared that it can be challenging to source enough organic grain grown locally because there are so few grain growers that are certified.

Further north, Maine Grains is milling local grain in Skowhegan, Maine. Maine Grains, founded by Amber Lambke, was launched in 2012 with the goal of solving the need for local infrastructure that could process grain into food-grade products. Amber explained that the infrastructure required to process grain was lost as grain production in the United States migrated west. Maine Grains repurposed a sturdy four-story county jailhouse for its mill which is USDA Certified Organic. Amber is excited about the coming years because she is seeing more and more businesses using local grain in their products.

Here in Connecticut, we can find an array of pasta makers and bakers doing just that. The care and effort Nicholas Imbriglio of Passionately Pasta in Wallingford, Connecticut places into all his products makes the name of his business ring true. He uses Ground Up Grain to create his pasta including his absolute favorite: Culurgiones, a handmade Sardinian ravioli. His favorite variation is his “Fully Loaded Baked Potato Culurgiones” which is filled with potato, in-house roasted garlic, sour cream, bacon, parmesan cheese, and chives. For Nicholas, the reason for sourcing local grain is clear: “If I wanted to serve pasta to my family, I would want to make the best pasta possible. Using local grain allows me to control the amount of local flour that I mill which in turn allows the freshness of the flour to remain. It has much more flavor, much more nutritional density, and those are probably the two biggest reasons that I do it. You taste the difference.” Recently, Nicholas has been offering pasta classes where people can learn how to create sheeted pasta such as spaghetti, fazzoletti, pappardelle, or fettuccini, plus a stuffed pasta typically made with a cheese filling. Participants are treated to a four-course dinner after they make their pasta.

In Deep River, Connecticut at Eight Mile Meadow, Jessica Chmura uses Ground Up Grain and Maine Grains for her pasta and baked goods. When Jessica started her bakery and pasta shop three years ago, she started thinking about what she wanted her business to look like beyond just the creative aspect. She knew she wanted to feed people nutritious food that benefited the local economy. The decision to use local and organic grains was part of that process. Jessica especially enjoys making her seeded porridge loaf as well as her honey oat loaf featuring organic oats from Maine Grains and southeastern Connecticut wildflower honey from local beekeeper Drew Burnett of Drew’s Honeybees in Norwich, Connecticut. Jessica is conscious of the fact that local and organic products can come at a higher price than food that is mass-produced in unsustainable ways. “I want to make my food available to all people rather than just people that have a higher income. How do I keep myself afloat and support the community as a whole? I think a lot of us wrestle with that.”

Dave Vacca of Nana’s Bakery and Pizza in Mystic, Connecticut is enthusiastic about incorporating the wide variety of grains that Maine Grains provides, including khorasan wheat, also known as Kamut, which is a highly nutritious ancient whole grain high in protein. As their name implies, Nana’s Bakery and Pizza also creates award-winning pizzas which are often adorned with seasonal ingredients sourced from local farms. A unique category of food that Nana’s is incorporating whole grains into is their delicious sweets. “You can add percentages of those whole grains into doughs and replace some of the white flour and you can really up the nutritional value of that donut or cinnamon bun or cookie,” Dave notes. For example, they bake a cookie that has rye flour in it. Another local ingredient Dave uses is eight row flint corn from the Davis Family Farm on the Pawcatuck River. The farm has been in the family for nearly 360 years and they grow corn that is native to the area. Dave dusts the peels of his bread using the corn meal, and makes corn bread, as well as polenta.

Jess Chmura of 8 Mile Meadow with a loaf of her bread; the Rice Koji cookie at Nana's, courtesy of James Wayman (Photo by James Wayman)

Spruce and Rye by Joe and Liza Padellaro is a new micro-bakery in West Hartford, Connecticut crafting baked goods that have a European flair. When it comes to grain, they have a clear favorite: rye. “It’s a powerhouse. Every product we bake features rye flour to some degree. That led me to follow old recipes and try to find a way to modernize them for aesthetics, or taste profiles,” Joe explains. Their Icelandic Rúgbrauð (rye bread) has a rich flavor with a touch of sweetness and is sprinkled with delicious seeds. They have been searching for different organic grains and enjoy using Skagit 1109 and a varietal called Expresso, a cross between Express and the hard red spring wheat Yecora Rojo. Although they are currently sourcing some of their grain from the Pacific Northwest’s Skagit Valley, they are eager to continue exploring the local grain economy and using more ingredients that are closer to home.

The local, organic, grain movement is growing and there are food artisans throughout Connecticut who are committed to making high-quality, local grain the cornerstone of their products. Farmers, millers, pasta makers, and bakers are working symbiotically to feed our communities. As conscientious consumers, we must rise to the occasion so the local grain economy can continue to grow.