Creating Food to Creating Knives

(left) Chef knife in AEB-L stainless steel. Hidden tang frame handle construction made from dyed and stabilized curly maple and black g10; (right) 6.5” Brute de Forge Damascus Santoku made from 51 layers of 1095 and 15N20 high carbon steel. Hidden tang frame handle construction with stabilized curly maple, black g10, and stabilized leopardwood.

A chef’s knife is not only the most important tool for the profession but the most iconic image. A chef needs to have know-how, creativity, and technique, since a good cut or slice of meat, fish, vegetables, or cheese can completely transform the experience of a meal from both the chef’s and diner’s perspective.

So, would anyone question the investment of a great tool? And who better to create such a tool than someone who has also spent many years cooking?

Michael Rubin is on the early side of knife production with his company Black Cap Blades, after cooking for years in restaurants and more recently, full-time on a food truck. Feeling the need for a transition three years ago, and with a desire to start his own business, he set his sights on a new path but knew he still wanted to be on the periphery of the food industry. What started out as a fun class to take with his wife, at Dragon’s Breath Forge in Wolcott with blacksmith Matthew Parkinson, turned into an endless “rabbit-hole” of intrigue, motivation, and especially, learning. He consumed everything he could, started gathering tools, created a workshop, and got to work. ough he relied on feedback from early customers, many of whom were friends and former colleagues, that trial and error period quickly took his skill and technique to where the business is now. Today, the orders for his knives are rolling in. At the time we met, he had requests to fill that would take production up through March 2022! And, as a one-man band making custom orders by hand, every hour is precious.

A good chef’s knife is expensive; but when you understand the process, watch the phases of production; and realize the effort it takes to produce one beautiful piece that could last a lifetime, the investment and value makes all the sense in the world. Depending on the type of knife or custom request, BCB knives can take from 15-60 hours to complete.

Michael puts his work and goals in terms of the good and the great and what separates the two. “The great things are the ones that wow you because so much care and dedication has been put into them. For me, every knife, at every single step, is executed with that level of dedication and attention to detail. I want to make extraordinary knives that help people to make extraordinary food.”

Chelsea Frost, otherwise known as PieGirlNJ, is one of those people. According to Michael, her pies are “mind-blowing,” and he’s proud to say she has some of his best knives. Chelsea shares the same level of passion for Rubin’s work: “I had originally ordered a chef's knife and gave Michael free reign on the handle, knowing that it would be beautiful.” She continues, “He went above and beyond. It's more gorgeous than I could have ever imagined. I ended up getting a matching paring knife to go with it. It is by far the most comfortable knife I've ever held. The curved spine seems like such a simple detail, but it makes all the difference. To top it all off, he engraved it with PieGirl and that was just the icing on the cake. Or the crumb top on my pie!”

Jumping from a kitchen, with the bustle of people, service, and direct connection, was not easy, however. Michael is slowly but surely making new connections and finding new ways to garner that “end-of- service” feeling of accomplishment with both home cooks and other chefs. He says his orders to each group are approximately 60% and 40%, respectively. Appropriately, his first order came from a childhood friend, Chef Daniel Miessner. Now freelancing (@acooksjourney on Instagram), Daniel has the first three knives Michael ever made.

Progressing a young business amidst the pandemic, obviously, has posed some challenges. We know the food industry has been hit hard, and therefore, some of Michael’s early customers were in a tough place. So, soon after getting started, the business was put on pause until being in the kitchen as a home cook or chef ramped up again. While BCB was on hold, Michael got back to cooking for a time and, with some friends, started delivering hot meals to homeless shelters around the state. They also collected donations from others to help defray costs of food and containers. After a few months, when cooks and chefs were really back in business, so too was Black Cap Blades; it was time to get the production line rolling again.

Despite the many downsides to running a business during the pandemic, in terms of creation and technique, Michael says that’s when he hit his stride. Of course, one thing the pandemic has given many people has been time to perfect their craft or learn a new one. For example, executive chef Matt Kneedland, with the Toro Loco Restaurant Group, ordered a knife from Michael during the pandemic. “From the moment I reached out to him he was great. He was super responsive during the planning process and my knife turned out better then I could’ve imagined. The handle is extremely clean and comfortable; the blade is easy to sharpen and has patinaed beautifully. On an average week, I butcher well over 100 pounds of beef and chicken, and my Black Cap knife is always the first knife I reach for.”

- Explore more at www.blackcapblades.com

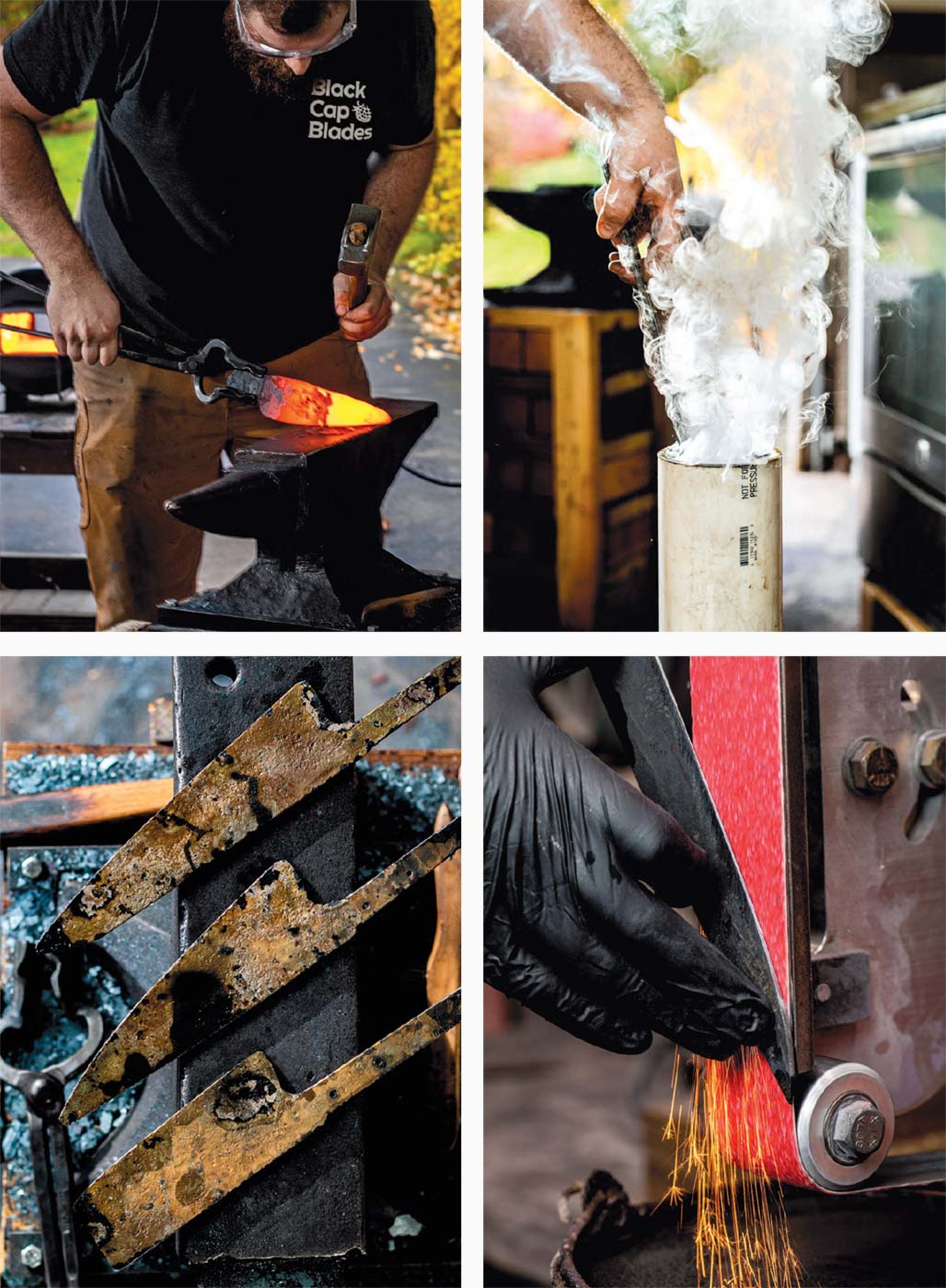

Top left: Forging out the tip of a chef knife.Top right: Oil quenching a knife Bottom left: Forged, profiled, and heat treated set - Bread knife, chef knife, and nakiri Bottom right: Grinding a primary bevel on a forged 10” slicer

MAKING A BLACK CAP BLADES KNIFE

By Michael Rubin

There are basically two main approaches to knife making, forging and stock removal. For the majority of my work, I use the stock removal method.

It all starts with the steel. You need consistent ingredients to make consistently good products. The steel comes in large sheets, and I will process it down into as many corresponding knife profiles that I can get out of that particular thickness. For example, I don’t use the same thickness of steel for a paring knife as I do for a chef knife. Once I have those profiles ground out of the steel I can mark and drill holes for a number of purposes; some for hidden pins, some for weight relief, and some for epoxy to form a bond through to each side of the handle material for added strength.

Next the steel needs to be heat treated with a specialized electronic kiln that allows me to control the temperature in an extremely precise and controlled way. This is necessary for controlling grain size and structure within the steel. The steps in this process are also what takes a relatively soft steel that can be machined somewhat easily to an extremely hard steel that can only be machined with carbide and diamond tools or aggressive abrasive belts.

Once the steel is hard it is ready to be ground. Along with the heat treatment, the bevel grinding dictates how the knife will perform. The grind can make the difference between a meat cleaver, a vegetable cutting laser, or an everyday workhorse knife that will do a bit of everything. It is time consuming and tricky to learn, but it is a large part of what separates handmade knives from factory made knives. The very edge of your knife only begins to split the food. The geometry of what comes directly after that edge is what dictates how the knife will move through the food, the tension of the cut, the pressure required, the release of the food sticking to the side of the knife, everything.

At this point the knife is ground to what will be 99% of the final geometry. The knife being this far along allows me to put an edge on the knife to check the cutting performance and make sure it is moving through food exactly as I expect it to. Because I haven’t done any finishing yet, I am not losing time if I need to go back and make any adjustments.

This is where hand finishing comes in, another touch that can set a knife apart from others. I like to round and polish the spine and choil of all of my knives. These are the parts of the steel that your hand will come in contact with the most, after even 30 minutes of cutting these are the features that if they weren’t rounded and polished would give you blisters or callous your hands over time. These also take sharp angles out of the steel to eliminate unnecessary stress points near the tip of the knife where things can be more fragile. Hand finishing also includes hand sanding the faces of the knife, this changes the direction of the scratch pattern and makes for a beautiful satin finish.

From here it is on to handle work. In the background I have been drying, processing, stabilizing, curing, and sanding wood to prepare for handle scales. All of that allows for a much more stable handle that will stand up to the elements of a kitchen much better. Not the dishwasher though, never the dishwasher. The handles are attached with high strength epoxies as well as hidden pins within the handle. They are shaped on the grinder and by hand and then also finished and polished by hand.

Each knife is then double- and triple-checked for fit and finish as well as checked for comfort in the hand in multiple grip positions and cutting actions. Once everything looks good the knife can receive its final cutting edge via hand sharpening on whetstones and leather strops to achieve a shaving sharp edge.

The only thing left is etching the company signature into the blade and to coat the blade and handle in a food safe natural wax to seal the handle and the steel from moisture. At this point the knife is photographed, packed up, and sent to its new home.